[ad_1]

Introduction

Good quality school-based relationships and sexuality education (RSE) has a key role to play in providing young people with information, motivation and skills to enhance their sexual health (UNESCO Citation2018a). Despite there being a national curriculum in Australia, each state and territory is ultimately responsible for school curriculum in both the primary and secondary school context (Carman et al. Citation2011; O’Rourke Citation2008; Ezer et al. Citation2021 Internationally and throughout Australia, teacher training organisations do not routinely provide education and training on RSE (O’Brien, Hendriks, and Burns Citation2020; Ezer et al. Citation2021), further contributing to wide variability in the extent and quality of RSE provision within schools (Ezer et al. Citation2021b; Goldfarb and Lieberman Citation2021).

Contemporary, international evidence advocates for a comprehensive approach to RSE in schools, that considers the enhancement of sexual health in addition to the prevention of sexual health problems (UNESCO Citation2018a; Mark, Corona-Vargas, and Cruz Citation2021; Sladden et al. Citation2021; Zaneva et al. Citation2022). Research clearly demonstrates that the comprehensive delivery of RSE has a positive impact on the sexual health knowledge, attitudes and skills of school-aged youth (UNESCO Citation2018a; Goldfarb and Lieberman Citation2021). A whole-school approach is recognised as the best-practice model for delivery of RSE (UNESCO Citation2016, Citation2018b). Such a holistic approach expands upon direct classroom instruction, to ensure the broader school culture is supportive of RSE and reinforces key RSE messages. Critically, it also requires schools to collaborate meaningfully with local services and families (Sawyer, Raniti, and Aston Citation2021).

With these issues in mind, the perspectives of parents are the focus of the work outlined in this paper. Perceptions of parents’ opinions and their anticipated reactions to the curriculum can influence the delivery of school-based RSE (Goldman, Juliette Citation2008; Marson Citation2019). Qualitative research on RSE implementation in Europe and North America has shown how RSE stakeholders overwhelmingly ‘highlighted the role of parents and caregivers as a source of opposition [to this work], whether at an individual school or broader community level’ (Marson Citation2019, 107). In contrast, other international research has consistently found parents to be supportive of RSE in schools. This includes findings from a systematic review of international studies (Kee-Jiar and Shih-Hui Citation2020) and later large-scale surveys conducted in the USA (Kantor, Levitz, and Syed Citation2017), Canada (Wood et al. Citation2021) and Croatia (Igor, Ines, and Aleksandar Citation2015). There is also evidence of supportive parental attitudes in traditionally conservative countries such as Bangladesh (Rob et al. Citation2006), Iran (Ganji et al. Citation2018), Malaysia (Makol-Abdul et al. Citation2009) and Oman (Al Zaabi et al. Citation2019).

Whilst Australian studies have reported similar results, they have generally lacked nationally representative samples. In 2009, 117 Australian parents completed an online survey with 97% of participants supporting school-based delivery of RSE and most wanted education to commence in primary school (Macbeth, Weerakoon, and Gomathi Citation2009). In 2010, a qualitative research study conducted in Western Australia found most parents of adolescents wanted sexual health education covered in secondary schools, but wished to be informed about the content (Dyson Citation2010). In the State of Victoria, with parents of primary school students, only a small number of parents believed that sexual health education should be left to families to deliver, but even these parents agreed that not all parents would be willing or able to pass on such information to their children (Robinson, Smith, and Davies Citation2017).

More recently, qualitative interviews with parents of primary school students living in Queensland found that they were generally supportive of RSE in the primary school context (Moran and Van Leent Citation2021). There has also been a nationwide online survey completed by 612 fathers with children aged 3–12 years (Thomas et al. Citation2021). Whilst this study did not specifically address school-based delivery of RSE, it did highlight that fathers strongly valued several sexuality-related ideals for their children and some findings were further associated with gender of the child, religiosity of the parent and/or socioeconomic status (Thomas et al. Citation2021).

Finally, an online survey of 2,093 parents in Australia who had a child currently enrolled in a government school, asked parents to share their general attitudes towards RSE, their opinions on who should provide RSE to young people, and their desire to be involved with school-based RSE (Ullman, Ferfolja, and Hobby Citation2021). Parents were also asked at which stage of schooling specific RSE contents areas should be covered. This work had a specific focus on gender and sexuality, with more than 80% of parents endorsing schools to address diverse gender identities and sexualities (Ullman, Ferfolja, and Hobby Citation2021).

The present study intends to build upon the current evidence base, to examine the attitudes towards school-based RSE among a national sample of parents (or caregivers) of school-aged children across Australia, that is inclusive of all school sectors. The study replicates much of the methodology and data collection tools recently used by a research team in Canada (Wood et al. Citation2021) to enable future cross-country comparisons. Specifically, the study sought to address the following research questions:

-

How supportive are Australian parents towards school-based relationships and sexual health education (RSE)?

-

Do Australian parents support the inclusion of a wide range of RSE topics?

-

At what year level do Australian parents support specific RSE topics being introduced?

-

How do Australian parents perceive the quality of the RSE that their child/ren currently receive/s?

-

For all research questions above, are any differences associated with demographic factors such as locality, gender of parent, religious background or political affiliation?

Materials and methods

An online survey was developed and administered, based on similar work recently undertaken in Canada (Wood et al. Citation2021).

Sample

Participants were recruited by The Online Research Unit (The ORU), a professional market research company with ISO-accreditation. The ORU manages a proprietary panel of over 350,000 respondents across Australia who are incentivised to participate in online surveys. Respondents receive points for completing a survey, based on overall survey length, and these are redeemable for gift vouchers. The ORU was contracted to provide a random sample of at least 2,000 survey responses from across Australia, with approximately half males and half females. Geographic location aligned closely with recent Australian Bureau of Statistics estimates.

Instrument

The Canadian data collection instrument was replicated closely in this current study. Slight amendments were made to the wording of some items to better suit the Australian context. Prior to survey administration, a series of brief cognitive interviews were conducted online with a diverse sample of ten parents to confirm content validity. Some amendments to terminology amendments were made. Most importantly, the term sexual health education was replaced by relationships and sexual health education. Notably, both these terms differ slightly from the phrase relationships and sexuality education, which is the nomenclature currently used in the Australian school context.

The survey questionnaire comprised four sections. Section one (five items) asked parents to confirm that they had a child currently attending a primary or secondary school in Australia, the school sector(s) attended, if any of their school-aged children had a disability and, if so, had it been formally diagnosed. They were then asked for their level of support for the statement: relationships and sexual health education should be provided in schools (response options: strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, strongly disagree, or I don’t know/prefer not to answer). Section two listed 40 RSE-related topics that schools could potentially address. The list of topics closely aligned with the Canadian research and included issues focused on minimising risk as well as those seeking to enhance wellbeing. The order of these topics was randomly generated and different for each respondent. Parents were asked to indicate the grade level at which they felt a school should start teaching that topic (response options: kindergarten-2, 3–4, 5–6, 7–8, 9–10, 11–12, this topic should not be taught, or I don’t know/prefer not to answer). Section three (16 items) asked a series of attitudinal statements regarding school-based RSE (response options: strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, strongly disagree, or I don’t know/prefer not to answer). Parents were also asked to rate the quality of current RSE provision that their child/ren had received in school, their level of comfort discussing RSE issues with their child/ren, and the frequency of these conversations in the past year. Response options all involved a 5-point Likert scale. The final question in this section took the form of an open-field text box in which parents could share any comments related to relationships and sexual health education in schools. Section four (8 items) asked parents to respond to a variety of demographic questions including their age, gender, ethnicity, locality, religious affiliation, and political affiliation.

Data analysis

The process of data analysis closely approximated that of the Canadian study. A respondent had to complete all five sections of the survey for their data to be included. Descriptive statistics were calculated for all demographic and key variables, and any missing data was noted. For the variable examining overall support for school-based RSE, strongly agree and agree categories were collapsed. Similarly, strongly disagree, disagree and I don’t know/prefer not to answer were collapsed.

To examine levels of support for each of the 40 proposed RSE topics, the total percentage level of endorsement was calculated for the overall sample and for each state/territory. Topics were also ranked based upon the grade level at which the majority of parents felt a topic should first be addressed. Response categories were also recoded to primary school (K-6), secondary school (7–12), or not at all, so that regional differences could be examined.

Finally, to examine the interactions between demographic variables and responses to questions of interest, cross-tabulations were conducted using Pearson’s Chi-Square test and Bonferroni adjustments as necessary. The data analysis process and results related to the general attitude items, parental comfort to discuss RSE, and the open-field qualitative data that was collected will be reported separately.

Ethical considerations

The ORU randomly notified all panellists who had previously indicated upon registration that they were the parent of a child aged 18 years or less. They were given a detailed Participant Information Sheet to read before providing consent and commencing the survey. Their decision to participate in the survey (or not) did not affect their relationship with the ORU, and they were free to skip items or to withdraw at any point prior to final survey submission.

This research project was approved by the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (HRE2021-0483) and all survey responses were de-identified by the ORU prior to forwarding to the research team for analysis.

Results

Data were collected during a two-week period in November 2021. The final response rate was 10.5% from distributed links and the median length of survey completion was 8.8 minutes. The final sample size was 2,427 participants, and just over half the respondents were female (56.5%).

Respondents lived in a variety of states and territories across Australia, and the majority had a child enrolled in a government school (67.8% in a primary school, 57.8% in a secondary school). Several respondents noted that they had a child with a physical disability (2%), an intellectual/developmental disability (11%) or both a physical and an intellectual/developmental disability (1%). For these parents, 89% had received a formal diagnosis. Most identified their ethnicity as Australian (61%) and possessed an undergraduate university degree or higher (58.5%).

The most common religious affiliations were no religion (38.7%), Catholic (21.3%) and Anglican (11.1%). The majority of participants rated religion as not at all important to their everyday life (40%), and 18% considered religion to be very important. Voting preferences were 26.7% for the Australian Labour Party, 25.1% for the Liberal/National coalition, 5.9% for another party and 23.6% undecided ().

Table 1. Demographic characteristics.

Although the demographic variable had options for trans- and gender-diverse people to self-identify, only one person identified as non-binary and so was excluded from the analysis due to insufficient power. In addition, all those who selected I don’t know/prefer not to say for the gender item were excluded from analyses for the same reason.

Support for school based RSE

Overwhelmingly, 89.9% of parents strongly agreed or agreed with the statement that relationships and sexual health education should be provided in schools. Whilst some variability was identified across different states and territories, this difference was not deemed to be statistically significant (p = 0.07) (). Females were more likely to either strongly agree and agree with the above statement than males and this difference was significant (females 91%, males 88%, p = 0.04).

Table 2. Parental agreement that relationships and sexual health education should be provided in schools, Australia and states/territories.

Participants who indicated that they had no religious affiliation were significantly more likely to either strongly agree or agree with the statement than those who were religiously affiliated (p = <0.001). Conversely, those who were affiliated with Islam or selected other religion were significantly less likely to strongly agree or agree with the provision of RSE in schools than all other participants (p = <0.001). There were no significant differences related to level of support towards school-based RSE and any of the other religious affiliations.

Those who considered religious affiliation as very important, were significantly less likely to endorse the teaching of RSE in schools (p = <0.001). Conversely, those who indicated that religion was not at all important were more likely to endorse this statement (p = <0.001). There were no significant differences found for those who rated religion as somewhat important or not very important.

Separate analyses were conducted for parents who identified as Catholic, specifically because this group is represented by its own school sector within Australia. Amongst all parents who identified as Catholic (n = 518, 21.3%), cross-tabulations were run to examine the relationship between strength of religious affiliation and support for school-based RSE, but no statistically significant differences were found (p = 0.61). This meant that there was no association between the strength of an individual’s affiliation to Catholicism and their attitude towards school-based RSE.

Those affiliated with the Australian Labour Party were more likely to strongly agree or agree with the statement above (p = 0.005). Conversely those who voted for other parties were significantly less likely to show support for this statement (p = <0.001). No statistically significant differences were found regarding level of support for school-based RSE and affiliation with other political parties.

Support for specific RSE topics and grade level for implementation

There were high levels of endorsement across the 40 listed RSE topics (supplementary materials Table A). Amongst all respondents, only three parents selected this topic should not be taught for all 40 items. Even the four topics with the lowest levels of support were still extremely well supported by parents overall, these being: information about masturbation (87%), gender identity (86%), abstinence (86%) and sexual pleasure (84%). Teaching about sexual orientation was supported by 89% of all respondents.

Breakdowns were also provided for each state and territory, indicating that support for each RSE exceeded 80% in all instances, and in many instances there was 100% agreement for certain topics to be delivered by schools.

Data was then reconfigured to highlight the grade level at which parents felt a topic should first be introduced (supplementary materials Table B). The majority of parents felt that seven topics should first be addressed during primary school grades: bodily autonomy and personal boundaries (e.g., a child’s body belongs to themselves); the correct names for body parts, including genitals; personal safety (e.g., abuse prevention); body image; self-esteem and personal development; changes associated with puberty (e.g., physical, biological, psychological, emotional, social); and communication skills. Most parents then felt that the remaining 33 topics should first be taught in grades 7 or 8.

Perceived quality of school-based RSE

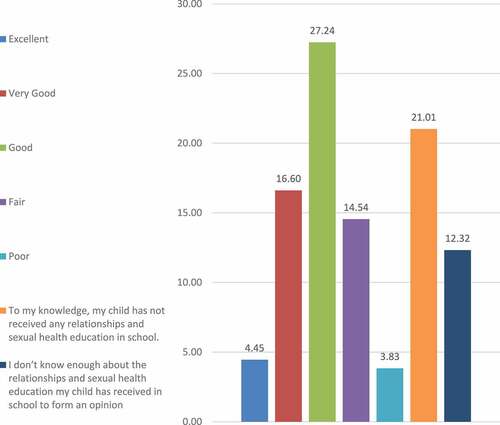

The majority of parents rated the current quality of their children’s school-based RSE as good (n = 661, 27.2%) (Figure 1). More than one-fifth indicated that they did not believe their child had received any relationships and sexual health education from school (n = 510, 21.0%), and these respondents were more likely to have a child enrolled in primary school (n = 487). These results did not differ significantly by state or territory (p = 0.11).

Figure 1. Parents response (%) to the item “Overall how would you rate the quality of the relationships and sexual health education that your child/children have received in school?.

Discussion

Support for school-based delivery of relationships and sexuality education

This study is the first national examination of parental attitudes towards school-based delivery of relationships and sexuality education (RSE) within Australia that is inclusive of all school sectors. Across all states and territories, there was resounding support from parents for schools to deliver RSE in both primary and secondary schools. Critically, the survey utilised a stratified random sample drawn from the ORU’s proprietary panel. This sampling frame has greater scientific rigour than a convenience sample (Crosby et al. Citation2009).

These results replicate previous international findings, clearly demonstrating that parents and families are highly supportive of RSE within schools (Al Zaabi et al. Citation2019; Ganji et al. Citation2018; Kee-Jiar and Shih-Hui Citation2020; Makol-Abdul et al. Citation2009; Wood et al. Citation2021), as well as a recent study of Australian parents who had a child currently enrolled in a government school (Ullman, Ferfolja, and Hobby Citation2021).

Gender differences were modest but significant. Women in the study were more supportive of school-based RSE than men. This aligns with previous studies that have shown women to take on the role of sexuality education in the home more readily than men (Flores and Barroso Citation2017). Thomas et al. (Citation2021) provide a robust summary of the current literature surrounding fathers as sexuality educators. They also challenge the media to provide a more positive and evidence-based portrayal of parental attitudes, in an effort to consolidate RSE efforts (Thomas et al. Citation2021).

Whilst it appears that support for school-based RSE varies slightly across the country, differences were not statistically significant. Some religious and political differences were also evident. Critically, despite the rhetoric that Catholic families are not supportive of schools delivering RSE, this was not supported by the data in this study. Even Catholic parents who were strongly affiliated with their religion, overwhelmingly supported school-based delivery of RSE. In contrast, Islamic parents were more likely to withhold support for RSE and this is a phenomenon that warrants further investigation.

This work appears to the first effort to document the possible associations between political affiliation and support for school-based RSE within Australia. Parents affiliated with the centre-left Australian Labour Party were most likely to support school-based RSE.

Internationally, it is recognised that religious institutions and conservative political parties are active opponents of school-based implementation of RSE (Ketting and Ivanova Citation2018). Whilst such groups are also known to drive resistance towards RSE programmes in Australia (Ezer et al. Citation2019; Shannon and Smith Citation2015), it appears these groups are overstating the level of dissent held by their members. Within this study, the vast majority of parents who either identified as Catholic, or as supporters of the Australian Liberal/National Coalition (i.e., a political party that generally advocates for conservative policies) were also highly supportive of schools to deliver RSE.

Support for schools to address specific relationships and sexuality education topics

Beyond overall support for school-based RSE, when parents were presented with an extensive list of possible RSE-related topics, there was overwhelming support for schools to address all areas. Whilst some parents were less supportive of schools providing education specifically related to abstinence, gender identity, masturbation, and/or pleasure, it should be noted that support for these topics still exceeded 80%. There was also a trend for most parents to nominate that most areas of RSE are best suited to the secondary school context. Similar data were recently reported by Ullman, Ferfolja, and Hobby (Citation2021). Whilst the parents in their sample only represented the government school sector, they also strongly endorsed the inclusion of a range of specific RSE content areas (n = 18). However, for 5 out of 6 broad content areas, most parents felt schools could address these issues within the primary school context (Ullman, Ferfolja, and Hobby Citation2021).

Taken together, these findings provide some interesting challenges for those working in RSE advocacy. Further effort may be required to inform parents, schools and the general public of the evidence-base regarding school-based RSE, specifically the best practice principles related to content and timing of delivery.

The International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education (Revised Edition) outlines eight key areas of RSE that all schools should address: (1) relationships, (2) values, rights culture and sexuality, (3) understanding gender, (4) violence and staying safe, (5) skills for health and well-being, (6) the human body and development, (7) sexuality and sexual behaviour, and (8) sexual and reproductive health. It argues that all these concept areas can and should be addressed in age appropriate ways from the first years of schooling (i.e. ages 5–8 years) upwards (UNESCO Citation2018a). Interestingly in this study, the majority of parents felt that most RSE topics should first commence in grades 7–8. Concerted effort may be needed to show both school staff and families that there are age appropriate ways to introduce RSE concepts in the earliest years of schooling.

Although 14% of parents indicated they did not want schools to provide education about abstinence, this finding should be viewed cautiously. The authors assume these parents likely did not want schools to provide an ‘abstinence only’ perspective in their RSE. This is based on the finding that support for schools to provide education regarding contraception and safer sex skills exceed 95% nationally.

Lessons that affirm diversity of sex, gender or sexuality have traditionally been challenging areas for schools for schools to address (Ullman, Ferfolja, and Hobby Citation2021; Ezer et al. Citation2021b). Sadly, it is widely known that current school-based delivery of RSE within Australia fails to affirm these diverse identities, and members of these populations report feeling unrecognised and disconnected from the school system (Strauss et al. Citation2017; Hill et al. Citation2021; Smith et al. Citation2014; Jones Citation2016). Based on the findings from this study, schools should feel confident that they have significant parental support to affirm non-heteronormative perspectives. However, continued work is required to better understand dissenting viewpoints.

Whilst various curricula in Australia espouse a strengths-based model that seeks to help students identify and apply individual skills relevant to their learning needs (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority Citation2022; Government of Western Australian, School Curriculum and Standards Authority Citation2022; NSW Government, NSW Education Standards Authority Citation2022; Victorian Government, Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority Citation2022), students and teachers report that health lessons seldom include notions of pleasure or sexual wellbeing (Ezer et al. Citation2021b; Fisher et al. Citation2019). While some parents remain uncomfortable about schools addressing sexual pleasure and activities such as masturbation, it is critical that RSE discourse moves beyond a framework that prioritises fear-based messages, which do not align with evidence-based principles (UNESCO Citation2018a; Mark, Corona-Vargas, and Cruz Citation2021; Sladden et al. Citation2021; Zaneva et al. Citation2022). Recent literature has also encouraged a move away from a risk-based approach, towards a framework of adolescent sexuality programmes that focus on healthy sexuality and sexual wellbeing (Kågesten and van Reeuwijk Citation2021).

Current discourse in Australia has focused on the importance of strengthening education efforts related to respectful relationships and consent (Marson Citation2021), and the most recent national curriculum review provides clearer guidance to schools in these areas (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority Citation2022). Whilst these topics are worthy of inclusion and attention, it is critical that all stakeholders appreciate that comprehensive delivery of RSE involves many additional areas of focus and has many positive outcomes in addition to reducing violence against women. Based on the findings presented here, schools should feel confident that parents are highly supportive of schools addressing a wide array of topics, including the correct naming of body parts, skills to engage in safer sex practice, skills to critique social media and sexually explicit imagery, and affirmation of diverse gender identities and sexualities.

Perceived quality of school-based relationships and sexuality education

Similar to recent findings in Canada (Wood et al. Citation2021), most Australian parents perceived the quality of current RSE provision in schools to be good, as opposed to very good or excellent. Significantly, in both countries, it was common for many parents to either report that their child had not received any RSE at school (15.7% Canada, 21.0% Australia), or to state they did not have enough knowledge about school RSE programmes to provide an opinion (8.4% Canada, 12.3% Australia).

The notion that Australian schools could improve RSE efforts is widely supported by sexuality educators (Ezer et al. Citation2021b) and young people themselves (Fisher et al. Citation2019). Beyond improvements to mainstream education, significant effort is required to provide RSE that is culturally appropriate (Mukoro Citation2022) and affirms young people living with disability (Frawley and O’Shea Citation2020; Michielsen and Brockschmidt Citation2021; Strnadová, Danker, and Carter Citation2022).

In accordance with evidence-based guidelines (UNESCO Citation2018a), it is critical that all Australian schools keep families informed regarding RSE delivery, so that school-based learning can be reinforced by home-based discussion. The recent work of Ullman and colleagues has shown that 68% of Australian parents within the government school system are keen to be involved with their child’s school-based RSE (Ullman, Ferfolja, and Hobby Citation2021). Keeping parents informed about the RSE programmes offered by schools also aligns with a key tenet of the whole-school approach (Sawyer, Raniti, and Aston Citation2021). To strengthen the alliance between parents and schools, Australian schools might look to legislative changes recently enacted in England. Here, in addition to the mandatory provision of Relationships Education in all primary and Relationships and Sex Education in all secondary schools, each school must also develop a specific RSE policy in consultation with parents (Department for Education Citation2019).

Strengths, limitations and future directions

Whilst the sampling frame used in this study enabled a large sample size and a diverse range of participants, there remain several limitations that warrant discussion. Some of these limitations were previously identified by our Canadian colleagues (Wood et al. Citation2021).

Although location proportions closely matched population level data, the sample may not be truly nationally representative based upon other characteristics such as gender or age. Furthermore, baseline population data pertaining to Australian parents who have a child currently enrolled in a primary or secondary school is not available for direct comparison with this sample.

Despite strong representation nationally, capturing a greater number of parents within each state and territory would enable more specific statistical analyses to be conducted at this level. The ORU specifically oversampled parents within Western Australia so that a specific report could be generated for this region. Future work may benefit replicating this approach nationally, particularly because primary and secondary schools are managed at the state government level. It will be particularly useful to establish if there are any state/territory-specific issues related to parental support towards RSE.

When parents were asked to rate the overall quality of RSE provision, this item did not account for multiple children, who would likely sit across different grade levels and may attend different educational institutions. Additional research should seek to better understand what specific factors lead a parent to rate their schools’ provision of RSE as anywhere from excellent to poor. Comparisons should also be made between parental perceptions of RSE delivery in comparison to the quality of other learning areas. The list of RSE topics (n = 40) that was given to parents provided no detail regarding how each topic might be delivered at particular grade levels. This additional detail may have influenced responses.

Whilst potential participants were randomly approached by the ORU to complete this survey, some level of response bias is still possible. Parents with either strong views towards school-based delivery of RSE, either positive or negative, may have been more likely to complete the survey. We have no information regarding the parents who opted not to participate.

Finally, this online survey was administered at a time when there had been a significant and ongoing discussion in Australia regarding teaching about consent in schools, and a sustained focus on issues related to violence towards women and children (Hendriks Citation2021; Kang Citation2018; Mathews Citation2021; Williams Citation2021) It is possible that these events may have influenced the way participants responded to the survey items.

The authors have made several recommendations throughout the discussion regarding how schools and RSE advocates should interpret and apply these findings. Further to these points, it is important that future research uses qualitative approaches to better understand the perspectives of certain sub-populations. For example, we need to better understand how to respectfully and effectively engage families with strong religious affiliations or diverse cultural backgrounds. There may also be additional challenges faced by families living in regional areas, and families with a child who is living with a disability. Implementation of school-based RSE will be greatly improved if we better understand these unique perspectives.

[ad_2]

Source link